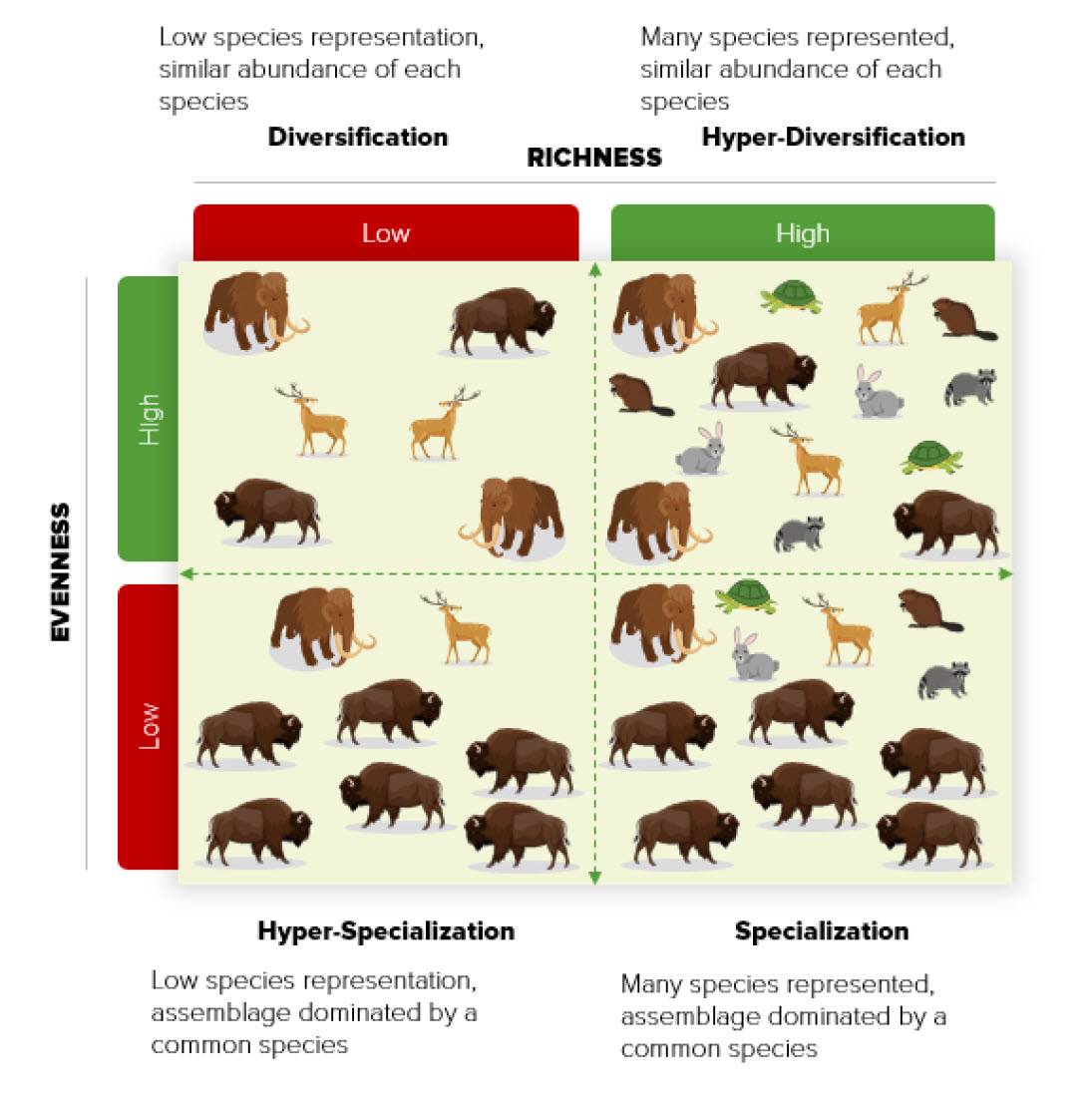

Boresup’s Theory of subsistence intensification is that as human populations grow, they give up “efficient” food-producing behaviors to increase the total food yield over a given unit of time or space. Anthropologists have vigorously debated this concept during the latter part of the twentieth century. They have proposed that dietary specialization and dietary diversification are two mechanisms responsible for subsistence intensification trends over time. On the North American Great Plains, archaeologists attribute the observed record of human dietary variation of at least 13,000 years, partially to the effects of human agency, temporal and regional variability in environmental conditions, and human and prey population dynamics. Despite this variation, an apparent big-game hunting specialization persisted in this region alongside more diversified strategies, until much later than in adjacent areas. This interpretation of specialized bison hunting proposed by early archaeologists likely fueled two widespread hypotheses: A) that prehistoric Great Plains indigenous people’s lives were highly contingent on the vast herds of bison that roamed the region, and B) that through time, a simplified progression of subsistence intensification took place. This progression begins with highly specialized big-game hunters during the Paleoindian period (13,500–9,000 BP) and culminates with a much more diversified economy during the Late Prehistoric period (1000–300 BP) that included foraged and domesticated resources. However, these inferences remain unevaluated across the Great Plains’ vast geographic range and its complete cultural chronology. To assess them, we employ a large dataset of dietary remains and investigate the broad patterns of dietary specialization and diversification used by Great Plains indigenous people over the past 13,500 years. Our analyses led to a twofold conclusion: 1) we find that even though prehistoric indigenous people of the Great Plains maintained a way of life associated with bison over time, bison was not the dominant hunted species in their diet; and 2) the hunting strategies and dietary variation that we observed on the Great Plains, through time, does not support a model of progressive resource intensification from hunting and gathering to farming. Instead, the data support a model of constant diversification of hunting strategies from the Paleoindian through the Late Prehistoric periods. In this model, hunters on the Plains (and elsewhere) maintained a consistently high resource diversity. We propose that this highly flexible and diversified portfolio of dietary strategies enabled the Great Plains people to successfully adapt their approaches to procuring food across different habitats and periods.